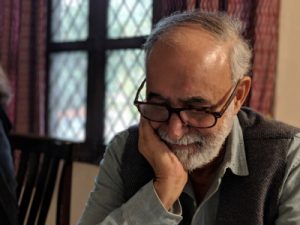

“It was such a powerful performance that I immediately decided that I wanted to make a film on it. I barely knew any filmmaking at the time, but the story had to be told — so I just did it. There was an effort to get funding, etc. but nothing panned out. That was also the time when DSLRs were just becoming popular for filming, so I bought one and started shooting,” remembers the filmmaker, who finished the film ‘Badshah Lear’ in 2018-19 but owing to the pandemic, could not screen it.

Now showing the movie, reflecting the tragedy of land against the madness of its ‘rulers’ at different venues, Anant, who grew up in Delhi says his introduction to Kashmiri culture came when along with his father, he made a film on Kashmiri Sufi music for which they would go to the Valley every season.

The young director admits it took him several years to finish the film as he kept second-guessing whether his effort was “worthy”.

“Also, having been rejected for funding multiple times from various documentary forums, working practically by myself on it, there were times I did feel as if it was just me who was interested in this story. I am not going to lie, it was quite a struggle internally.”

In many ways, the film is not just about the Bhands but also operates on different layers — the Pandit exodus, the idea of ‘Kashmiriyat’, and censorship among others. In one of the scenes, M.K. Raina says, “After several years, when I visited my ancestral house in Kashmir, it was locked. I knocked a few times and then returned. I cannot describe how I felt. Houses remain, we perish.”

Anant had abandoned the initial plan for the film because it just was not turning out to be “interesting”. He then let the footage lead him to a story. Adding that censorship emerged as a theme without him planning for it as it is inherent in the story of the Bhands, he says, “I have an intense dislike for hierarchy and authority because it only serves to narrow down the human experience. Art is diametrically opposed to that because it is about freedom, expanding our experiences, and seeing the world in newer ways. For me, this story in particular is a tale about the resilience of art tinged with melancholy as you realise that the battle of ideas is never really over. We need to constantly push back.”

The director, who comes from a culturally mixed home (mother being part Maharashtrian and Bengali, while MK Raina is Kashmiri), Anant, when asked if M.K. interfered with his creative process during the shoot of the film that unfolds through the latter’s eyes, laughs.

“One particular day, during the shoot, he kept giving instructions to one of the Bhands. At first, I told him that I was recording sound so he should not say anything. But he did not stop. I finally had to tell him angrily that this was my film, not his. Things were a bit tense for some time but it was smooth sailing later.”

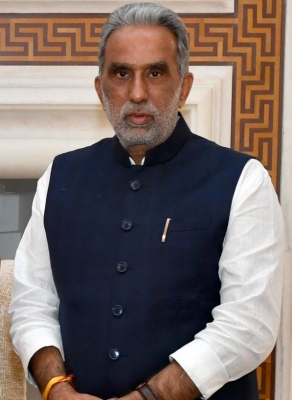

M.K. Raina tells IANS that for him the most striking aspect of the film is that it deals with a subject that, while being political, is not part of any discourse in the country.

“The natural way of unfolding of Kashmiri syncretic life without any underlying or deliberate attempts to propagate the ‘Kashmiriyat’ theme, and how it has vanished is established honestly. The celebration of culture as a resistance despite being marginalised in a wider violent political turmoil is the high point for me. I like his prologue and epilogue, his deliberately avoiding the often repeated Kashmiri pretty pictures landscapes cliche, which would have dwarfed the depth of the film. it is a very important document of the culture of the people for the people who work in conflict zones. One does not witness a black-and-white approach,” says Raina, who assures that he followed the son’s instruction as he would do for any director.

(Sukant Deepak can be reached at sukant.d@ians.in)

–IANS<br>sukant/khz/