New Delhi, March 8 (IANS) Scientists have for the first time detected the closest known relatives of Covid in more than 12 per cent of people living in rural Myanmar, indicating that “zoonotic spillover is occurring”.

An international team of scientists from US, Singapore and Myanmar screened the blood of 693 people in Myanmar between 2017 and 2020. The participants belonged to communities that engaged in extractive industries and bat guano harvesting from rural areas in Myanmar.

The findings, published in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases, showed that 12.1 per cent people were seropositive for sarbecoviruses — the family of Coronaviruses to which SARS-CoV belongs.

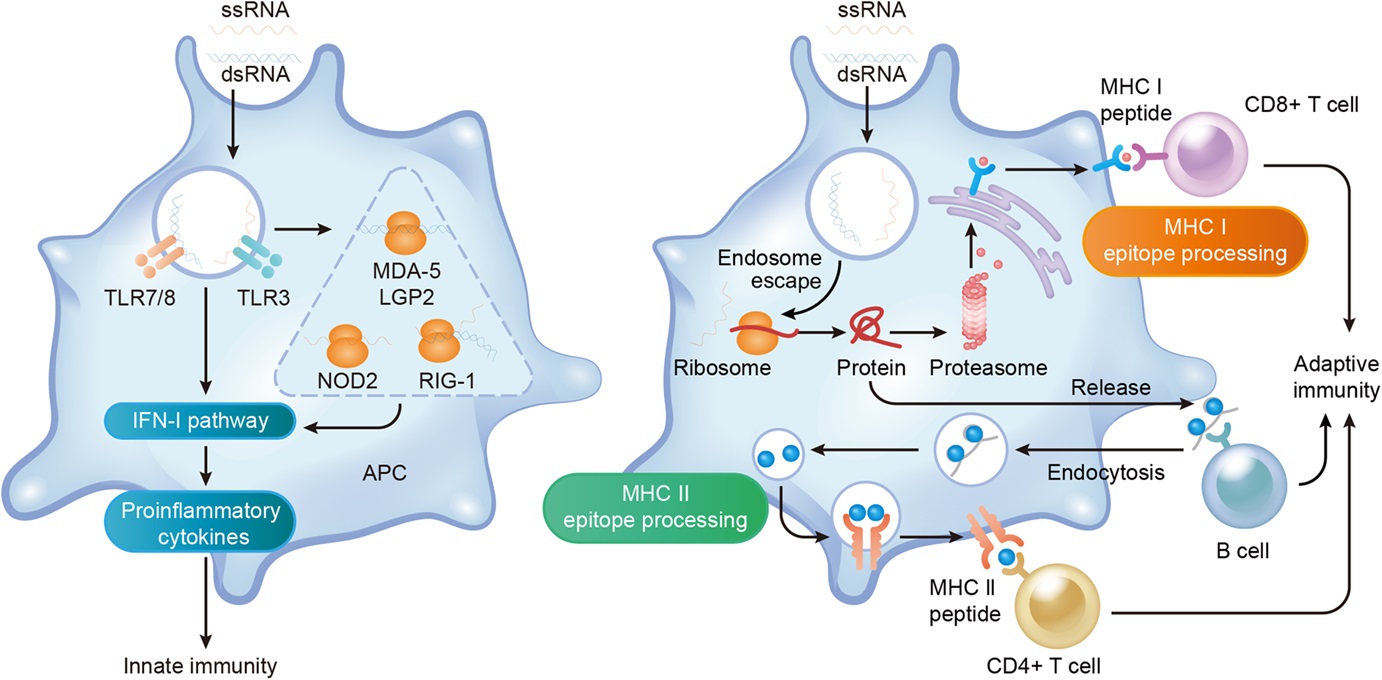

These viruses, with potential to jump from animals to humans, had never previously been detected in humans. They have so far been detected in bats.

“Exposure to diverse sarbecoviruses among high-risk human communities provides epidemiologic and immunologic evidence that zoonotic spillover is occurring,” wrote Tierra Smiley Evans, from University of California, and authors in the paper.

While the paper identified exposure to a range of bat and pangolin sarbecoviruses, the data suggests that RaTG13 is the sarbecovirus most frequently spilling over to people in Myanmar.

RaTG13, the closest known relative to SARS-CoV-2, was discovered by Pasteur Institute researchers in 2020, in a cave in Yunnan, China, along the border with Myanmar. It was 96.1 per cent identical to SARS-CoV-2 overall and the two viruses probably shared a common ancestor 40-70 years ago — similar to the new-found viruses.

Among a set of 70 samples taken from people working in elephant logging camps, 32 per cent had been exposed to RaTG13. About 1.4 per cent people were also found exposed to BANAL-52.

BANAL-52, which shares 96.8 per cent of its genome with SARS-CoV-2, was also discovered by Pasteur Institute researchers in 2021 from horseshoe bats in Laos.

“Our findings underpin the critical importance of continued surveillance at the rural wildlife-human interface in Southeast Asia, where some of the highest levels of known mammalian diversity exist and where future emergence of zoonotic diseases is likely,” the researchers said.

–IANS

rvt/uk/